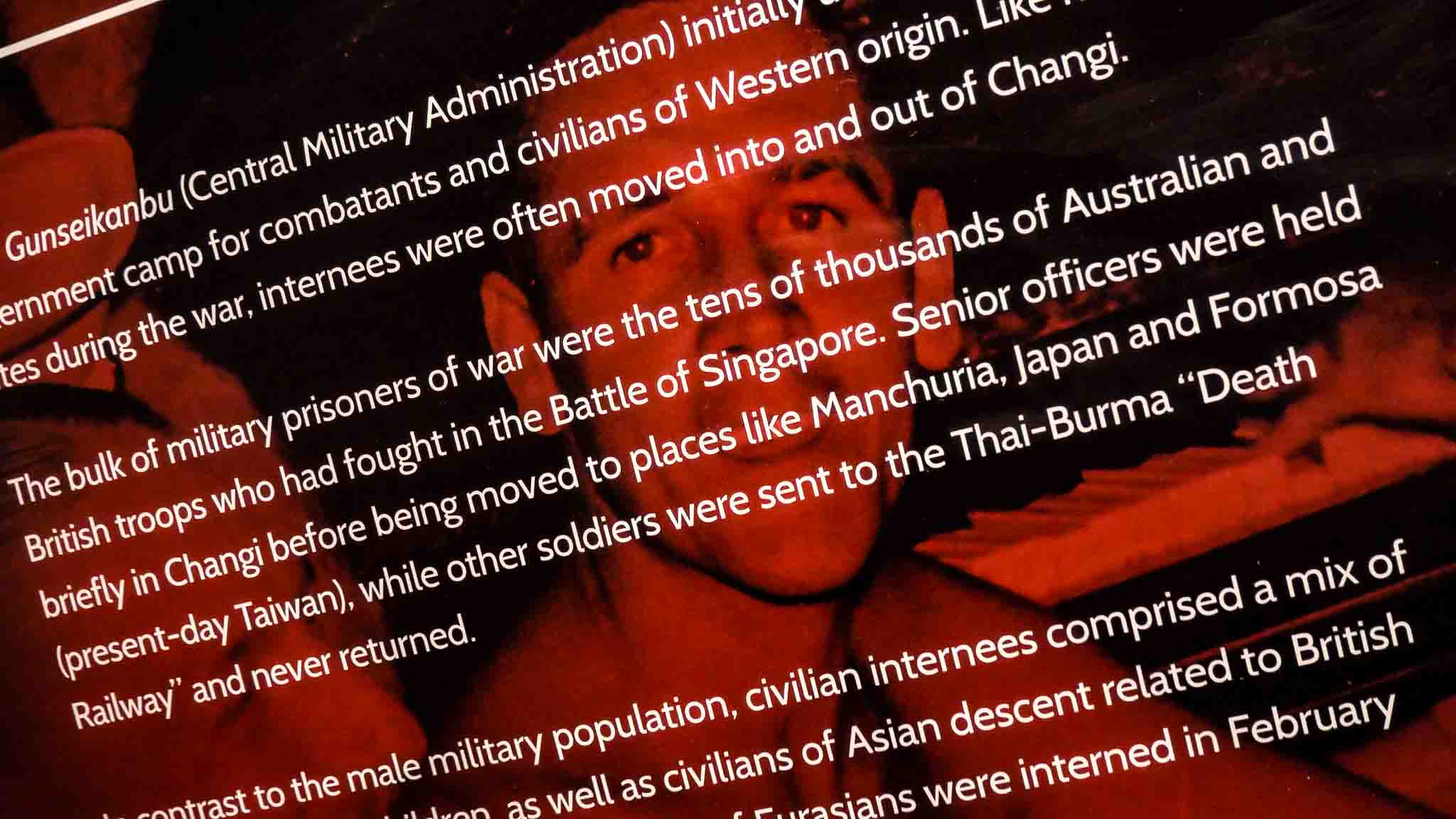

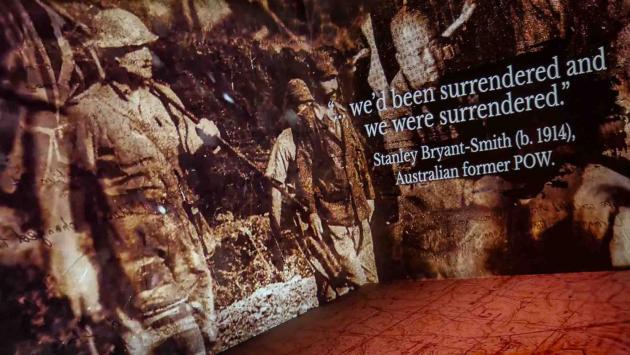

British and Australian travellers have been making the solemn pilgrimage to the small museum on the site of Singapore’s Changi Prisoner of War Camp for decades. The Japanese established the camp at what had been a British colonial military base, after the fall of Singapore in February 1942. Commonwealth prisoners from here were distributed to Japanese POW camps across Asia including the infamous Thai-Burma railway.

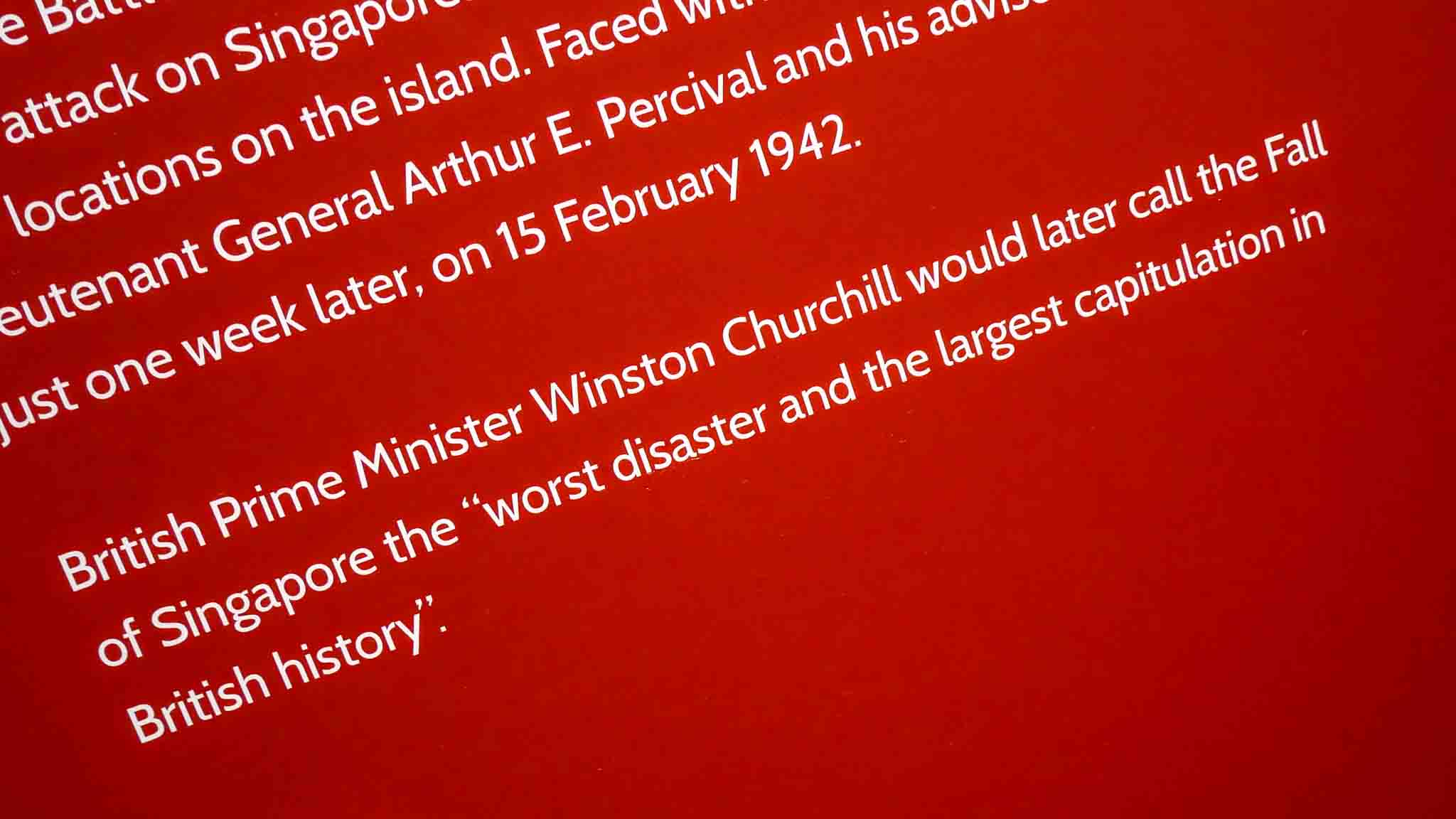

For British visitors, Changi Chapel and Museum is also a place to think about the Fall of Singapore - described by Winston Churchill as the “worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”. For Australians in 2025, a visit to Changi might also raise questions about what happens when a trusted and powerful protector can no longer fill that role?

Check out our video reflecting on Changi Museum and its connections to WWII history and Australia

As a museum, Changi is modest. That’s not a criticism. I like compact museums and often find their messages leave a bigger mark.

The terrible suffering of British, Australian, Commonwealth troops and the people of Singapore is what first engages your attention.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Changi Chapel and Museum, Singapore

Photo: Mark Bowyer Changi Chapel and Museum, Singapore

But sometimes museums also take you places they didn’t intend. My visit to Changi also got me thinking about how this devastating and sudden collapse of Britain's reputedly "impregnable" military stronghold in Singapore must have impacted back in Australia.

Since colonisation, Australia’s European inhabitants have had an acute sense of isolation. We’ve been soothed by the idea we have a big and powerful protector in the distance.

For more than century, our distant protector was our coloniser, the British. In February 1942, the Japanese shattered Britain’s imperial supremacy in our region in a week. Australia’s sense of security was shaken to the core.

With Britain bogged down in war in Europe, Australia was abandoned.

Fortunately for Australia, the United States, already at war with Japan, stepped in. Protecting Australia made sense in America’s plan to defeat Japan and avenge the shocking attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941. Australia provided a buffer and base. Stopping Japanese expansion was a shared interest.

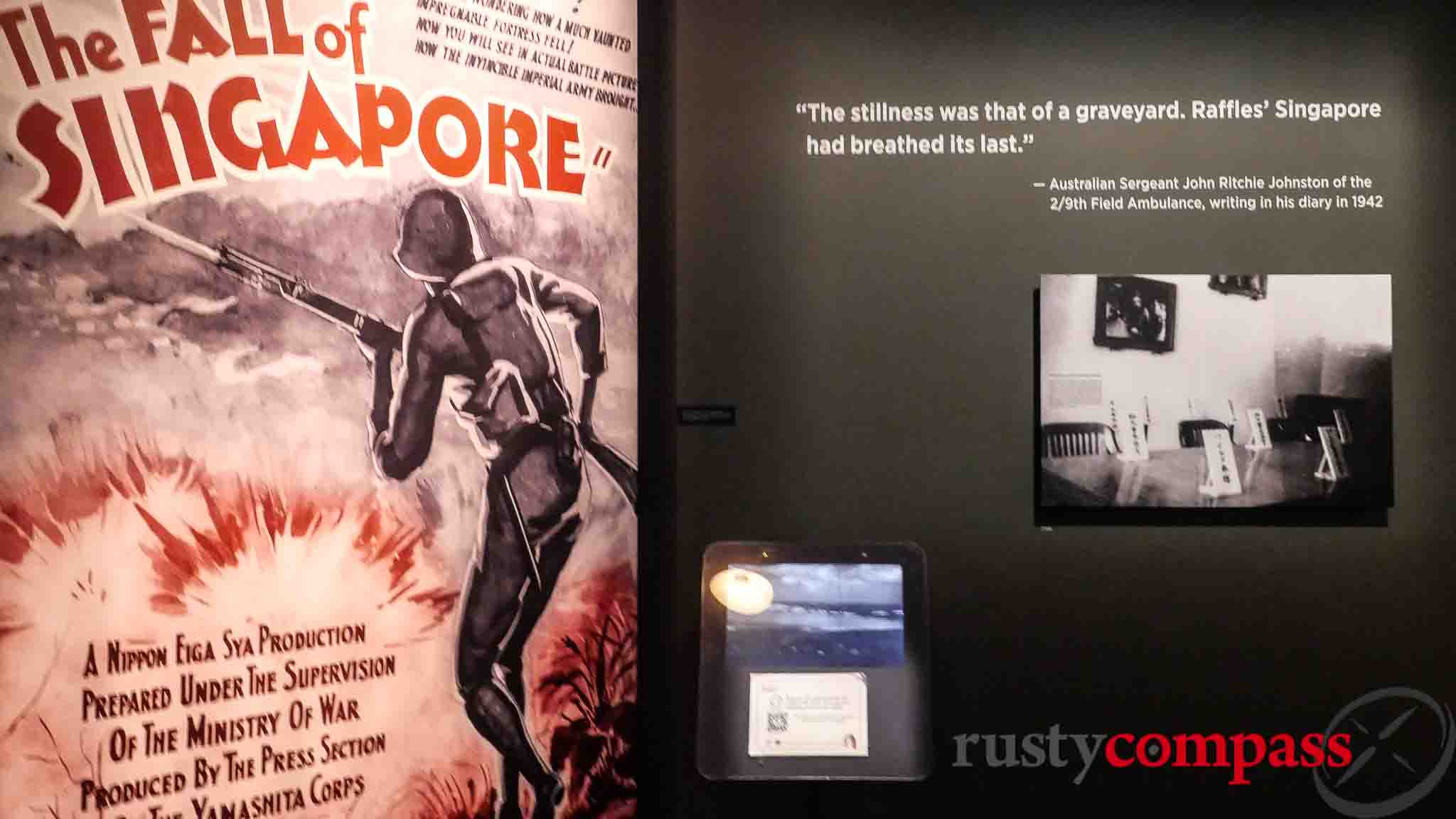

Photo: Mark Bowyer Singapore's National Museum also explores the 1942 Fall of Singapore

Photo: Mark Bowyer Singapore's National Museum

For more than 8 decades since the end of Word War II, the US and Australia have viewed Asia as a strategic theatre of central importance. The ANZUS alliance has defined our defence policies and our participation in global conflict. It’s made Australians feel safe and powerful.

These days, Australians are feeling less safe.

China is now a formidable military power. And Donald Trump’s distaste for America’s traditional allies and his meddling with Ukraine, NATO, Canada and Greenland, have shaken global confidence.

How secure should Australians feel? How well prepared are we for life without a big protector should that become our reality?

Way back in 1996, Paul Keating made one of his many landmark speeches. I’m sure the choice of Singapore as the venue was not an accident. He made two points. “Australia must find its security in Asia and not from Asia.” And “If Australia cannot succeed in Asia it can’t succeed anywhere”.

Soon after, Keating was booted from office. John Howard stepped in as Prime Minister for a decade and became known pejoratively as the US’ deputy sheriff.

Howard’s approach to the world, not Keating's, has defined Australia’s international policy since he left office in 2007. It's looking a tad fragile in 2025.

A visit to Singapore’s Changi museum will prompt some reflection on these big current matters. Just as museum visits should.

There are no comments yet.