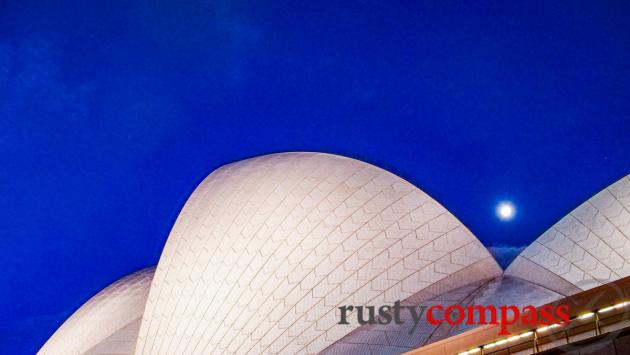

As it approaches its 50th birthday, Sydney Opera House is still loved by Sydneysiders and visitors as it was when Queen Elizabeth II opened it in October 1973. This is Australia's most popular tourist site, visited by more than 10 million people in non-COVID years. Many see shows, many more simply come to admire the architectural marvel.

The Opera House, like Sydney's famous Harbour Bridge, can be a recurring theme in your exploration of the city. See a show, take a tour, grab a drink and a bite, wander around in awe, admiring astonishing design and engineering feats. Then admire from afar - from Lady Macquarie's Chair in the early morning, and Waverton or North Sydney in the evening. And from around various vantage points like The Rocks, the Harbour Bridge, Milson's Point and a harbour ferry.

Photo: Mark Bowyer The bridge and the house from the Botanical Gardens.

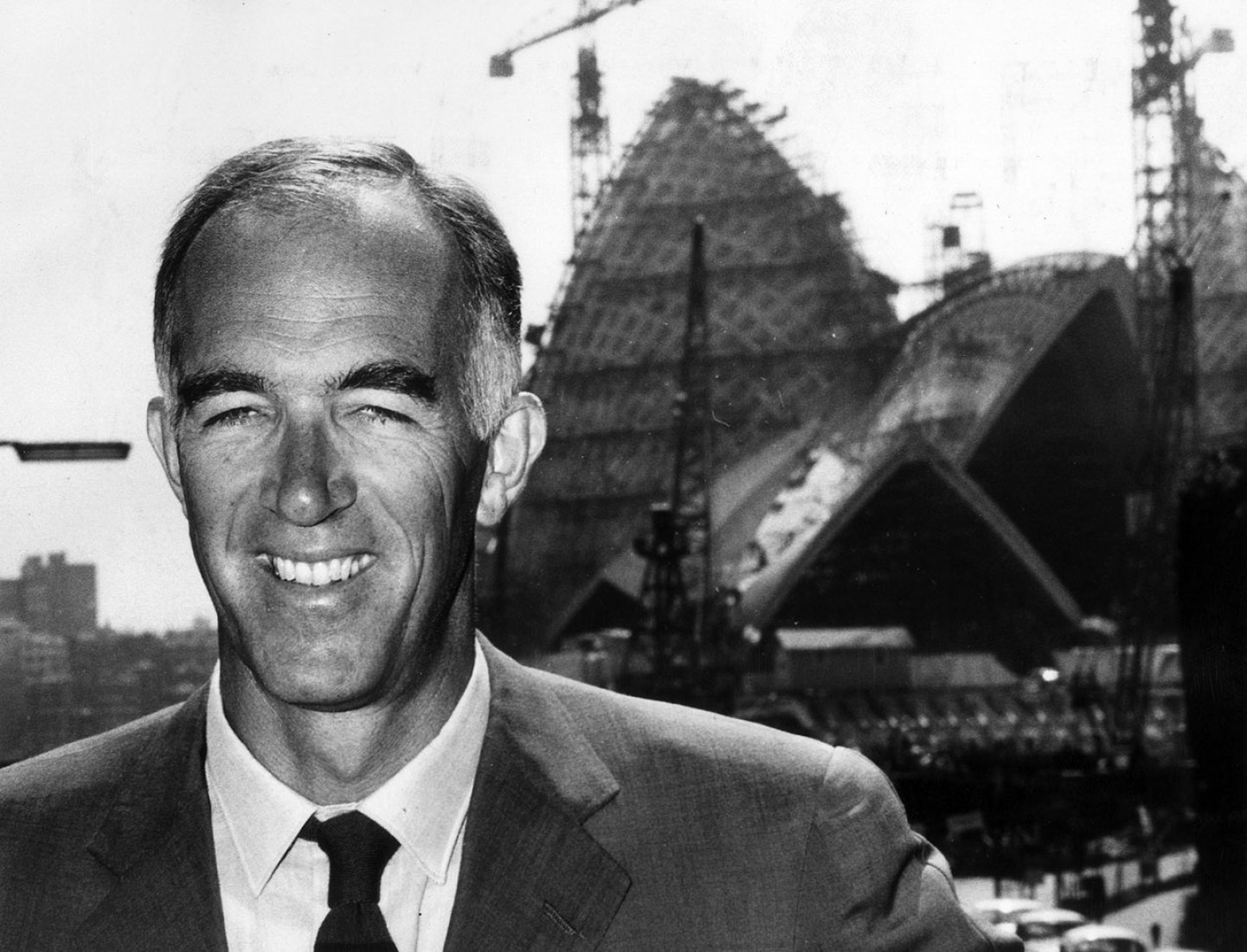

You'll get an appreciation of the genius of Danish architect Jorn Utzon. He created his masterpiece from Denmark, using photos, maps and diagrams. He didn't see the harbour for the first time until after he won a design competition for the project in 1957.

The Opera House gives to Sydney from every angle and its natural place in the harbour maybe Utzon's greatest architectural triumph.

The backstory to Sydney Opera House is a cracker. It makes the creation of this icon even more remarkable. It will leave you asking whether this remarkable building is a true expression of Sydney creativity and character, or a fluke born of a chance collision of people and events.

The Opera House does nothing but flatter Sydney, but the messy history of its creation, is less flattering, but no less helpful in building a picture of Sydney and New South Wales. (see our short history below).

It's easy to experience Sydney Opera House as a performance space or simply a global architectural landmark. Here are our tips for getting to know Australia's great creation.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Sydney Opera House

See a show at the Opera House

Sydney Opera House has six performance spaces and in normal (non-COVID) times hosts 2000 performances a year. There's everything from Opera and ballet to rock concerts and philosophy seminars, cinema and theatre. Check out what's on before you arrive in Sydney and book your tickets in advance. Many shows sell out.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Opera Bar - Sydney makes good use of its harbour.

Grab a drink at the Opera Bar

The Opera Bar on the western side of the Opera House is a must-see Sydney watering hole. It gets busy on spring and summer weekends. If you want to be sure, make a booking for a table on the water beforehand.

The views across the harbour to the Harbour Bridge as the sun goes down are unforgettable.

Drink prices are reasonable for the views and the setting. There's a menu of light bites available.

Take a wander around the Opera House

Even if your schedule doesn't allow you to see a show at the Opera House, take a good look at the exterior of the complex. Approach from the Botanical Gardens to the east. And when you've finished exploring the perimeter, head up the stairs for a close look at the sails. Getting up close is exhilarating.

The exterior of the Opera House, including the harbour side forecourt, is normally open for exploration and there's some seating if you want to take a break amidst some of the most photographed icons on earth.

Sydney Opera House runs tours of the complex - interior and exterior - including children's tours.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Up close - Sydney Opera House

Explore from afar

One of the real miracles of the Opera House is how perfectly it sits on Bennelong Point to form a perfect union with the harbour and the Harbour Bridge.

If you're staying downtown, make a point of admiring the Opera House from different vantage points. Walk through the Botanical Gardens to Lady Macquarie's chair for one of Sydney's favourite views.

Take a walk across the Harbour Bridge and explore the harbour foreshore for another perspective on the city. The views from the Harbour Bridge viewing points are pretty special too.

The Manly ferry also gives you a world class view of the Opera House and the harbour.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Afternoon at Sydney Opera House from Royal Botanical Gardens

Sydney Opera House chronology and facts

* The Opera House sits on Bennelong Point, named after one of the first Indigenous men to be captured by Captain Arthur Phillip's solidiers after the British invasion of 1788. Bennelong was taken by Phillip to England in 1792.

* Prior to the construction of the Opera House, Bennelong Point was a tram yard. Before that it was Macquarie Fort.

* The idea for an iconic Sydney opera house and performance space was first championed by Eugene Goossens, British-born composer and conductor in the early 1950s. His idea was taken up by Labor Premier and unionist Joe Cahill.

* By the mid-50s, Cahill was determined to make the Opera House happen, despite opposition.

* Goossens was lost to the cause in 1956. He left Australia embroiled in an occult and pornography scandal after an affair with the so-called "Witch of King's Cross".

* In early 1957, Danish architect Jorn Utzon won a design prize for the project with his radical "shell" design concept.

* Premier Cahill died in 1958 with a final wish that his controversial and costly dream project, be completed.

* Construction commenced in 1959.

* Utzon faced major engineering challenges that he successfully resolved amid delays and cost overruns.

* 1965 saw the election of the conservative Askin government. Askin and his party had been openly critical of the project. Davis Hughes, a trenchant critic, was appointed Minister for Public Works.

* Utzon resigned in 1966 after irreconcilable conflict with Hughes.

* Major protests ensued against Hughes and Askin in support of Utzon.

* Hughes took direct charge of the project, appointed Peter Hall as architect and made changes to Utzon's plans for the building interior, including the Concert Hall.

* The Opera House was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in October 1973, to global excitement. It was years late and massively over budget. The original cost estimate to build Sydney Opera House was $7 million. The final cost was $102 million.

* Construction was expected to take four years. It took 14 years and involved 10,000 construction workers.

* Goosens, Cahill and Utzon, the three men who were the key drivers of the project, were not acknowledged at the opening.

* The Opera House project was mostly fund by a State Lottery.

* Premier Askin, who had sought political gain for years by criticising the project, soaked up the glory of its opening.

* Twenty six years later, the Opera House made peace with Utzon, its Danish creator, in 1999, consulting him on future plans.

* In 2003, Iraq War protestors painted "No War" on one of the western sails of the Opere House.

* In 2007, the Sydney Opera House became the youngest UNESCO World Heritage listed site.

* Utzon died in 2008 having never seen the transformational building he designed.

* The Opera House has hosted all kinds of performance, from Lou Reed and Prince to Joan Sutherland and Pavarotti. There is a regular programme of opera and ballet and the Opera House is the home of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

* The Opera House steps and forecourt are used for major events.

* In the 1990s, an exclusive apartment complex known as The Toaster was controversially built near the Opera House. Shock-Jock Alan Jones and others, regularly complain about noise from Opera House concerts, unconcerned that Australia's favourite public space pre-dated their arrival by several decades.

Photo: Mark Bowyer The Sydney Opera House and its companion.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Sydney Opera House sails light up for the annual Vivid Festival

A brief history of Sydney Opera House

The two men who conceived and championed Sydney's Opera House, Premier Joe Joe JJ Cahill and celebrated British composer, Eugene Goossens, are unknown to most Australians. Their unlikely collaboration is one of the most endearing things about the complicated Sydney Opera House story. And their perplexing and little-recognised contribution to Sydney's icon is only the start of that story.

Joe Cahill was born in working class Redfern to Irish Catholic immigrants and worked in the NSW Railways before becoming an active unionist and joining the Labor Party. Cahill entered State Parliament in 1925 and became Premier of New South Wales in 1952. The optimism of the post-war era was building. Sydney's future prospects looked bright and Premier Cahill agreed with advocates like Goossens that the city needed a world class cultural institution.

Photo: Archival Queen and Premier Cahill in 1954. He wasn't mentioned at the Opera House opening in 1973

Cahill would provide the political momentum for the project but it needed an artistic advocate too. British-born Eugene Goossens, Conductor of the Sydney Symhony Orchestra and Director of the Conservatorium of Music was that advocate. Goossens was a man of international reputation, friend of Picasso and Noel Coward. He was insistent not only on Sydney's need for an Opera House (other than the acoustically flawed Town Hall), but that it should be located at Bennelong Point, the harbourside home it would ultimately get.

An earlier plan would have located the Opera House at Martin Place on Macquarie St.

In 1954, Joe Cahill was determined to proceed with the Opera House project. He said "the building when erected will be available for the use of every citizen, that the average working family will be able to afford to go there just as well as people in more favourable economic circumstances, that there will be nothing savouring even remotely of a class conscious barrier and that the Opera House will, in fact, be a monument to democratic nationhood in its fullest sense." They were lofty ambitions and the Opera House has exceeded Cahill's best hopes.

In 1955, Premier Cahill announced an international competition for the design of the Opera House. There were 223 entries from around the world. In early 1957, the winner was announced. A radical design from young Danish architect Jorn Utzon would reshape Sydney's harbour.

While the competition was under way, the project's unofficial artistic ambassador, Eugene Goossens, became embroiled in scandal. Though Goossens' scandal was only indirectly connected with the new Opera House project, it was the first of many controversies that would involve Sydney's iconic landmark. All shine a light on the post-war evolution of the city and the frailties of its powerful people.

In Sydney since the 1940s, Goossens had built the reputations of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and the Conservatorium of Music. But he had other non-musical interests. After picking up a book of occult art, he began an affair with artist and occultist, the "Witch of King's Cross" Rosaleen Norton.

Things turned bad for Goossens when he returned from Europe and faced a Customs inspection at Sydney Airport. Pornography and other occult paraphernalia were found in his luggage - all unacceptable in prudish 1950s Sydney. It was the end of Goossens distinguished career in Sydney and he returned to England before Utzon's successful Opera House design was selected in early 1957.

Construction of the Opera House commenced in 1959. There were problems from the outset. The geology of Bennelong Point wasn't as stable as hoped and engineering challenges posed by Utzon's unique design were still unresolved. Utzon ended up forming a vital partnership with British engineer Ove Arup. The Opera House project burnished the already-considerable reputation of Arup and his company.

Before the end of 1959, a political dilemma confronted the project. Premier Joe Cahill, its determined political patron, died aged 68. The project was beset by budgetary and engineering problems. The conservative opposition had become trenchant in its criticism. On his deathbed, Cahill called on his Public Works Minister, Norman Ryan, to ensure the project's success.

Engineering challenges persisted into the 1960s. Utzon proved equal to them and resolved the major obstacles himself. The most pressing engineering challenge concerned the roofing of the "sails". Engineers were baffled when Utzon came up with his "Spherical Solution". It meant a significant change in the design of the sails from that initially proposed, to the design we now know.

With his major engineering problem resolved, Utzon's challenges became political. His political crisis turned terminal when Robert Askin's conservative government was swept to power in 1965.

Askin and his party had been critical of the Opera House project for years and the new Premier appointed another staunch critic, Davis Hughes, as Minister of Public Works to oversee the project. Hughes got straight to work making life difficult for the idealistic Dane.

Photo: Archival Jorn Utzon - engineering problems resolved

Early in 1966, architect Utzon, the man most responsible for the creative wonder of the Opera House, would soon also be permanently severed from its future and Sydney. After an irreconcilable breakdown with Hughes, Utzon resigned and returned home. He never returned to Sydney and never saw the completion of his dream.

In 1968, Australian filmmaker John Weiley, living in London, was commissioned by David Attenborough, then at the BBC, to make a film about Utzon's falling-out with the Askin conservative government and the Opera House project. He created Autopsy on a Dream. The film was so explosive that the BBC ended up destroying it after a single UK broadcast. The film was assumed to be lost forever.

In 2012, a single print of Autopsy on a Dream was discovered in a BBC archive. It had survived the BBC censor's knife. Weiley got to work salvaging it and in 2013, it had its first Sydney screenings. It's a remarkable film about the Opera House, Sydney politics, Australia and the 1960s. I highly recommend it for an appreciation of the conflict and mishaps that befell the creation of one of the world's most extraordinary buildings.

After Utzon's departure, a government architect, Peter Hall, was handed the colossal responsibility of finishing the project. Minister for Public Works Hughes, a man with no experience in architecture or the arts, fancied himself as a director of the completion of the project. The Opera House interior ended up a long way from Utzon's plan and was considered a major compromise on the architect's vision. It wouldn't be corrected for decades.

On October 20 1973, The Sydney Opera House was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II. The opening ceremony was a global event. The three men most responsible for the project, Goossens, Cahill and Utzon, were not mentioned in the opening. Robert Askin, a man who had fought the project and made life difficult for Utzon, soaked up the glory of the day. It was not a pretty end to almost three decades of effort to create a world class Sydney arts institution.

Photo: Archival The Queen and conservative Premier Askin on opening day. The Opera House creators didn't get a mention.

The Opera House's international fame has only grown since its opening. It is recognised among the great architectural accomplishments of the twentieth century and became the youngest UNESCO World Heritage listed structure when it was added in 2007. For almost fifty years, Sydney Opera House has been an outstanding venue of classical music, opera, ballet, rock, jazz, folk, theatre, talks and cinema.

Like many school kids, I sang at the Opera House in high school in 1981. It was the same year I saw folk singer Donovan Leitch perform there.

In 1999, the Opera House sought to reconcile with Utzon and his vision. Utzon, in his eighties and frail, graciously agreed and sent his son Jan. Jan Utzon met Labor Premier Bob Carr in Sydney four decades after his father had met Labor Premier Joe Cahill to get the project rolling. He is said to have been wearing the same suit his father had worn in 1957.

The reconciliation made way for the reassertion of some of Utzon's original design plans for the Opera House interior. A major renovation ensued, overseen by Jan Utzon. Utzon senior, the great creator of Sydney's Opera House, died in 2008, aged 90.

The Opera House has continued to provoke controversy over the years. In 2003, activists painted "No War" on one of the sails to protest Australia's participation in the Iraq conflict. The sails have been co-opted by protestors on a number of occasions since.

The sails are also used to decorate Sydney on special occasions such as the annual VIVID festival. In 2018, gambling and horse racing ads also got a run - causing outrage among Sydney's arts community.

The Opera House forecourt has been used for major live music performances - usually pop and rock music, since the 1970s. Local favourites (Kiwis and Australians) Crowded House, have played some of the biggest forecourt shows.

In 2016, the residents of a building unaffectionately known as the Toaster, protested about the noise coming from the nearby Crowded House shows.

The story of the Toaster and the Opera House reveals a common thread through the life of this transformational project since its opening. It's a theme that was picked by John Weiley in his 1968 film.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Neil Finn concert on the forecourt and Sydneysiders having too much fun. Powerful new Opera House neighbours are opposed to such events. Opera Houses should be seen, not heard.

Many in Sydney had opposed the Toaster development, right by the Opera House, back in the 1990s. They believed the city's most important public space should be expanded in the public interest.

The Toaster was built decades after the Opera House began holding major outdoor events. Suddenly, in 2016 the new residents on Bennelong Point, were objecting to the Opera House being the arts venue it had been from the beginning. It was not missed that the Opera House's outdoor concerts attract a greater cross-section of the Sydney community than the more refined indoor shows.

Chief among the new residents complaining was the Sydney shock-jock, Alan Jones. Jones has wielded nasty-edged political power in Sydney, for decades. NSW politicians and Premiers are often more answerable to him than to their electors. And he's a reminder that the ghost of spoilers like Davis Hughes, the man who made Sydney life unbearable for Danish creator Jorn Utzon, are never far from surfacing in Sydney.

The tension between people like Jones and Sydney's creative and public spirit is important to understanding the city. The history of the Opera House is rich with that tension.

Looking around Sydney in the 2020s, the ascendancy of the wreckers like Jones, often seems complete.

I find myself asking, could Sydney ever do something as perfect as the Opera House again? Or was it a union of political, creative and cultural forces of the late 1950s and 1960s that can never be repeated?

There are no comments yet.