Saigon’s War Remnants Museum must be one of the most visited museums in South East Asia. I was told last week by staff that it's on track to receive close to 1.5 million paying visitors this year (consider this a rough estimate). Most of the guests are foreign tourists.

That’s a huge number of visitors for an old-school museum focused on telling the stories of a war that ended almost fifty years ago. The methodical way visitors inspect the collection, studying photographs and captions, would be noted with envy by museum curators everywhere.

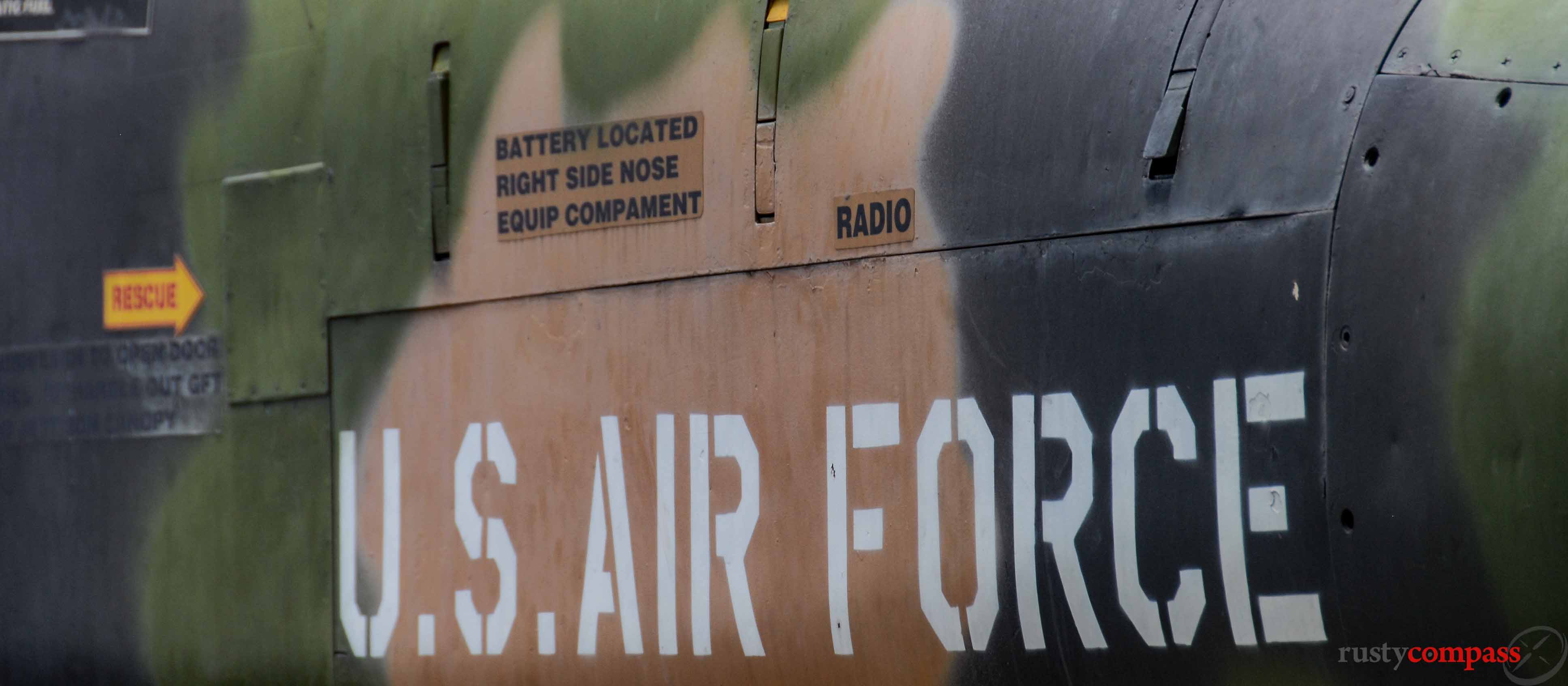

Photo: Mark Bowyer US aircraft - War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City

US aircrasft - War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City

From my quick check, 1.5 million visitors is more than any museum in Sydney receives. Only the Art Gallery of NSW - with free admission, big-ticket international exhibitions and a huge budget - receives more.

Saigon's War Remnants Museum is located in a neighbourhood not far from downtown Saigon, a few hundred metres from the former residence of US Commander General William Westmoreland. Visitors pay a little under $2USD, to walk halls of images depicting the horrors of the conflict known here as The American War. There’s no fancy technology - just words and images curated across three floors. Outside there’s a collection of military leftovers - aircraft, tanks and weapons.

General Westmoreland's former residence. District 3, Saigon (shot in 2008) © Mark Bowyer

There’s a War Crimes Gallery. Another tells of the continuing impact of unexploded ordnance, Agent Orange and other chemicals. Another retells the victorious war history. There’s a gallery focused on the international protest movement against the war. The Requiem exhibition is the most powerful. It features war photography by photojournalists killed from all sides of the conflict.

The appalling story of the My Lai Massacre of 1968 is retold. The less-known story of former US Senator Bob Kerrey’s participation in a massacre in the Mekong Delta in 1969 is also told. Kerrey (not to be confused with Secretary of State John Kerry), became a champion of reconciliation between the US and Vietnam after the war. His past role in the massacre did not become known until 2001.

Photo: Mark Bowyer Young crowd - War Remnants Museum Saigon

The museum's collection seems to be connecting with visitors. The young flock to the place with the same enthusiasm and curiosity as their parents.

In the 90s, I recall warning visitors that the museum would shock. That shock still comes in several hits. The brutality of the images is traumatising. We westerners are not accustomed to a museum experience where our brutality is so graphically depicted. And the Vietnam War is taught to us as one of failure and loss. At the War Remnants Museum, that same war, the American War is depicted as a brutal but righteous David and Goliath triumph.

The War Remnants museum has produced its fair share of indignation over the decades. There are, of course, omissions. Vietnam’s other wars with the French, Chinese and Cambodia get very little attention. The great famine of 1945, caused by the Japanese with the help of the French, must have been one of the greatest crimes of the twentieth century. It killed up to 2 million Vietnamese. I don't recall seeing any references to the famine. Korean war crimes are not widely referenced either.

One of the things I value most about travel is that it provokes self-reflection. It makes you question your assumptions. Often it makes me think about my home, Australia. This museum in Saigon makes me think about how we do history in museums in Australia and elsewhere? I’ve found myself asking the extent to which Australian museums are candid about our own past? How they treat the atrocities and systematic killing of Australia’s First Peoples, over more than a century, following colonial settlement?

With only fifty years of distance from their wars and suffering, the Vietnamese might reasonably claim their wounds are too raw for a completely dispassionate account? How do we explain our gaping omissions in the West?

When I first visited the War Remnants museum in the 1990s, it was known as the Museum of American War Crimes. At the time, Vietnam was still being punished by a crippling US economic embargo. In 1994, almost twenty years after the end of the war, President Clinton finally lifted the embargo and normalised diplomatic relations. Vietnam’s belated post-war economic recovery got properly under way. Sometime after that, the museum’s name changed. The narrative and gruesome images remain unchanged though. And the complex has expanded. Once the entire collection fitted in a small colonial era villa. These days it’s a big concrete complex.

Photo: Jacqueline Allen The original American War Crimes Museum in 1994

Photo: Jacqueline Allen Tanks at the original War Crimes Museum 1994

The War Remnants Museum is proof of the universality of history’s power and appeal at a time when it's being degraded across the western world in education and popular culture. For all the museum's shortcomings, it provokes visitors to think about an uncomfortable past that embroiled France, the US, Australia, China, Laos, Cambodia and others. The Vietnam War provides one of modern history's most absorbing and complex studies in politics, geopolitics and the Cold War. Many of the lessons are applicable today - especially our capacity to overlook the suffering of the disempowered. And Vietnam once again finds itself in the frontline of a new great power rivalry.

Special thanks to my former colleague and friend Jacqueline Allen for her 1994 shots.

Check out our independent travel guide to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) here.

Twice each year, Mark Bowyer leads Vietnam by the Book, a tour of history, stunning places and culture focused around three books. For more check out Old Compass Travel. We also operate tours of history and culture in Ho Chi Minh City and Sydney.

There are no comments yet.