Vietnam’s southward expansion through territorial conquest in the 16th century shifted the country’s political and commercial centre of gravity southward. During this process, the Nguyen family established supremacy in the south and it was the Nguyen Lords that began using Hue as a regional capital for their southern dominion from that time. Hanoi continued to be the national capital but a developing south and centre naturally needed a local political hub of its own - it was to be Hue.

The prelude to Vietnam’s last dynasty - Tay Son rebellion and the Trinh and Nguyen Lords

Photo: Mark BowyerThien Mu Pagoda is one of the earliest monuments in Hue

Quang Trung’s reign was short. He died mysteriously when preparing to crush a revival of the Nguyen Lords under Nguyen Anh in the south. His early death severely weakened the Tay Son movement and Nguyen Anh commenced a campaign to seize control of the country. He succeeded in 1802 and so began the Nguyen Dynasty with Nguyen Anh - known as Gia Long as emperor and Hue as capital.

The Nguyen Dynasty

The Tay Son period took a big toll on the Nguyen Lords and it was luck and tenacity that kept the young Nguyen Anh alive after most of his family was slain by Tay Son rebels. Nguyen Anh spent the early Tay Son period in Siam awaiting a chance to strike back at Tay Son rule. When the Tay Son forces reduced their Saigon garrison in 1788, Nguyen Anh seized the opportunity, attacked and reclaimed the city. It was the beginning of a long quest against Tay Son rule that culminated in victory and the unification of Vietnam under Nguyen rule 1802 with its capital in Hue.

The movement of the capital from Hanoi to Hue was in recognition both of the Nguyen Lords’ historic territorial base in the south as well as its increasing importance as migration swelled the population and commerce there.

While Nguyen Anh’s victory occurred with minimal foreign intervention, he had long sought French support for his imperial ambitions. Though the French showed only tepid interest at the time, they would be a perennial menace to the sovereignty of the Nguyen Dynasty as their interests in Indochina grew through the nineteenth century.

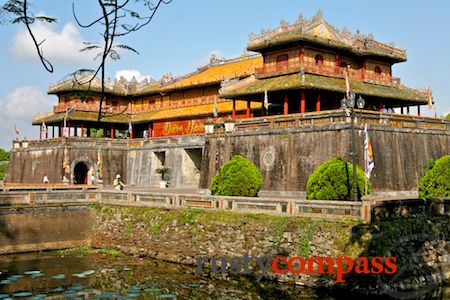

Photo: Mark BowyerNgo Mon Gate at Gia Long's citadel. It was here that Emperor Bao Dai abdicated in 1945.

Gia Long’s successor Minh Mang (1820 - 1840) was less enamoured of the French and was openly hostile to their proselytising. He issued edicts banning Christian religious activity that aroused French fury. This tension continued to simmer under the reign of his two successors Thieu Tri and Minh Mang.

It was Vietnam’s fourth Emperor, Tu Duc, who faced the ignominy of surrender in the face of full French military assault in 1858. From 1862, France established control of large parts of the country. Any last semblance of Imperial sovereignty was gone. The French position in Vietnam was secure and would continue to grow for decades.

Emperors Ham Nghi, Thanh Thai and Duy Tan all mounted resistance to the French. Ham Nghi only reigned for one year (1884 - 85) before becoming embroiled in a rebellion against the French. The French appointed his brother as his replacement. Ham Nghi was ultimately exiled to Algeria in 1888. He died in France in 1945 having had a family with a French Algerian.

Emperors Thanh Thai 1889 - 1907 and his son Duy Tan continued the tradition of resistance to French rule. Like Ham Nghi before them, both assumed the role of emperor at a young age and both quickly developed a dislike for French control of their homeland. Thanh Thai was also noted for his embrace of western cultural ways despite his contempt for French rule.

Both men were exiled. Thanh Thai died in Saigon in 1954 while his son Duy Tan died in plane crash in Africa on his way back to Vietnam. He was hoping to mediate in the collapse of the dynasty at the hands of Ho Chi Minh’s communist movement.

Photo: Mark BowyerKhai Dinh's Tomb, Hue

Khai Dinh’s son Bao Dai was to be the 13th and final Emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty. Best known for his pursuit of women, rare Vietnamese tigers and political legitimacy irrespective of its complexion, Bao Dai never managed to garner much respect from any quarter. He obliged the French before doing a deal with the invading Japanese Imperial Army. He dutifully abdicated in favour of Ho Chi Minh in 1945 expecting a role as supreme advisor to the newly formed Communist Government. His abdication marked the end of the Nguyen Dynasty’s tenuous 143 year rule but it did not mark the end of political dealing for Bao Dai. That occurred in 1955 when Premier Ngo Dinh Diem won a referendum appointing him head of state of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) with an implausible 99% of the vote. Bao Dai died in France in 1997.

And so ended the unsettled dynasty of the Nguyen only to be replaced by a period of greater instability and bloodshed as the French intervention in Vietnamese affairs was replaced by US meddling.

Landmarks -

Minh Mang, Tu Duc and Khai Dinh’s tombs are well worth visiting in Hue.

The Citadel, built by the first Emperor Gia Long is a must see sight. It includes the room in which Bao Dai abdicated in 1945.

Downtown royal residence of Cung An Dinh is also worth visiting for its connection to Khai Dinh’s reign.

Hue as conflict intensifies

While the Nguyen Dynasty’s last two Emperors were enjoying the fruits of their compliance with French demands in the decades before WWII, the seeds of decades more conflict were being sown in the tree lined streets of the imperial capital. Sporadic resistance to the French had arisen throughout the 19th century. By the twentieth century, the resistance was starting to show the influence of western enlightenment thinking. Vietnamese nationalists were being exposed to Rouseau and Voltaire and were watching developments across borders in China and Japan with great interest. One of the most important of these thinkers was long term Hue resident Phan Boi Chau. Phan’s Hue residence remains open as a shrine to his memory.

By the start of the twentieth century, a prominent Hue family, the Ngo’s has established an elite school in the city now known as Quoc Hoc - still one of Vietnam’s most prestigious high schools. The Ngo family’s prominence would turn international when their son, Ngo Dinh Diem became South Vietnam’s first President and America’s key ally in the fight against Ho Chi Minh’s communists.

Photo: Mark Bowyer,National School, Hue

When Ngo Dinh Diem became the first President of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) in 1955, it marked a continuation of centuries of dominance of Vietnam’s south by Hue’s dynastic families. Diem’s election victory was highly suspect - he won more than 99% of the vote - but that didn’t stop Lyndon Johnson praising him as the Winston Churchill of Indochina.

By the 1960s, Diem’s hometown was back in the international news. A devout Catholic, Diem ruled with an iron fist. He was helped by his two brothers, Ngo Dinh Nhu who ran the southern region and Ngo Dinh Can who presided over the central area around Hue. The brutality and corruption of Nhu and Can was legendary and Diem was constantly accused of favouring Catholics in the mainly Buddlhist country.

In 1961, religious tensions grew with the appointment of yet another Ngo brother, Ngo Dinh Thuc, as Archibishop of Hue. Thuc exercised great political power in the city. In May 1963 a ban on the flying of the Buddhist flag at an important religious celebration resulted in protests in which security forces opened fire on an unarmed crowd nearby the Tu Dam Pagoda killing nine.

Photo: Mark BowyerMonk Thich Quang Duc's Austin with Malcolm Browne's haunting photograph behind it.

On November 1 1963, a group of South Vietnamese Army officers captured and executed Diem and Nhu in a coup. Can was also arrested and executed in 1964.

Landmarks

Phan Boi Chau’s house

Quoc Hoc - National School

Tu Dam Pagoda

Dieu De Pagoda

Ngo Dinh Can’s former residence and grave.

The Battle of Hue 1968

The Battle of Hue was the longest and one of the most deadly and devastating of the Vietnam War. On the morning of 31 January 1968 as Communist forces launched their Tet offensive across South Vietnam, the city of Hue became the only city to fall. The Communist NLF flag was quickly raised over the citadel where it flew for 25 days until US marines and South Vietnamese forces reclaimed the city.

In some of the most intense fighting of the war, thousands of communist soldiers were killed as well as hundreds of South Vietnamese and US soldiers. Civilians also suffered terribly as door to door combat and Viet Cong reprisals against local government officials and their families took thousands more lives.

The city of Hue and its historic citadel were left in ruin by rocket fire and US aerial bombing. Evidence of the battle is still visible in the damaged citadel walls.

Photo: Mark BowyerThese huge urns are all that remains of the Forbidden Palace

It was seven years later on March 24 1975 that Communist forces again took control of Hue at the beginning of their triumphant march south to Saigon. On this occasion South Vietnamese forces were in disarray after confused messages were despatched from President Thieu in Saigon. There were no US marines or aerial bombings. Another era was beginning for Hue.

Landmarks

Hue Citadel still shows the scars of battle. There are few stretches of the citadel wall that do not show the impact of shell and automatic weapon fire.

Since 1975

Photo: Mark BowyerShell damage from Tet 1968, Hue Citadel

Hue’s heritage also suffered as a the highly ideological and cash strapped Communist Government saw little value in the relics of a humiliated imperial dynasty.

In 1993, Hue’s imperial ruins were inscribed into the World Heritage list and so began a tourism led revival that has driven renewed interest in the city’s past.

There are no comments yet.